Friday, 24 March 2023 // Women

8:43 PM

82.4°

London

The music across the street has ceased. The master of ceremonies no longer on the microphone.

I am mistaken. Five minutes later, the MC is back on the mic. But the volume has decreased. Now I hear a woman speaking and dogs barking in a neighboring yard. A motorcycle rides down the road, my room set back on one side, and across the street, where people have gathered for a batoki, a party.

The botaki started before I arrived back to my place, around 6:30. I’m told the party is to celebrate my neighbor’s menses. Just yesterday Tureta, the preschool teacher, the English teacher, I know in Tabwakea, told me she was thinking of me over the past few days, wanting to invite me to another botaki.

She was aware I was in Paris, Poland, but hoping I would be here for the party (botaki) that celebrated her niece’s menses, wanting me to bear witness to another Kiribati celebration. Tureta explained the botaki is not just for women, but for everyone.

I was aware that’s what the party across the street was for, with a remix of a Cyndi Lauper song blasting loud enough to wake the dead. I joked to Rodney Edwards, whose guest house I rent, that the kava bar was much too loud. What kava bar he asked? I pointed: the one across the street. He laughed.

Everyone laughs here. My slightest gesture, inflection, tone of voice, 100% lack of control of the language other than a half a dozen words, elicits laughter and smiles.

I note the waning crescent moon, hanging above the home across the street where the party is celebrated. And above that sliver of moon, a bright Venus, the evening and morning star.

I appreciate how the planet hangs above the home, with Venus and menses all on the same trajectory. The arc of women and timeless mythology.

Well, I was wrong again. It’s now 9 PM and the music has cranked up again, full volume. In spite of the volume of the music in the distance, I can hear the laughter of girls, with the master of ceremonies prompting more waves, gales of laughter. A smattering of applause.

I suppose it’s because I am I-Matang, a foreigner, that makes it easy for me to communicate. Not that I don’t have that same ease with boys or men, but back in the States I would not dream of engaging girls or women to the same degree I do here. Because I am I-Matang I am Novelty. I am accepted here. Honored.

I use that novelty to my advantage. When I walk into a store, a room, and all eyes turn to me, I offer a “Maori! Maori!” - hello, hello - and with an exaggerated bow, sweep my hat from my head, and earn smiles. The sweep, the bow, it’s not disingenuous, but heartfelt. I am honored with the attention. But I am the foreigner, and I want them to know I am grateful.

Many years ago, when my daughter was 14, we were standing on a rooftop on Second Mesa, on the Hopi reservation. We were observing the dance below. To my right, a woman, my age, about 45, held a baby. It was her great granddaughter. As she sat there, her daughter, 30, stood behind her. And her daughter, the daughter of the baby, a 15 year old sat with her grandmother.

Behind me, to my left, a woman asked was this my wife with me? No, I explained she was my daughter. I was surprised, that my daughter still had pimples, certainly did not seem of age for marriage.

Yet she was the same age as the new mother to my right. It took me only a moment to understand. This was not some “teen pregnancy issue,” that may be an issue in a local high school, or some American backwater. The fact is, the matrilineal Hopi have been following the same pattern for millennia. It is understood and excepted. There is a deep family bond. With the age of 15 comes motherhood.

I mention this in the context of the girls and women I see here on Kiritimati. When I meet my neighbor Angus’s 7-year-old daughter, Booto, she wears only a pair of shorts, and her toplessness would be deemed inappropriate back in the States. When I see her the next day, her hair in a long, neat, beautiful long braid, she is in her school uniform, as tidy as any other in her congregation.

In the bwia next to my house a teen mother sings to her baby in the sweetest way, gentle, lulling, in all hours of the day and night. I hear the singing days before I realize where it is coming from or why.

My first full day on the island happens to coincide with International Women’s Day. I am told the parade starts at 7 AM and I am there at 6:30 AM, by the large municipal parking lot and community stage. I have not yet learned about Kiritibati time. Everything will be an hour late.

It is now 9:20 PM and I hear silence across the street. But let me get back to my story.

I am the only in I-Matang sitting with the dozen or so people in the folding seats, watching the half dozen church affiliated schoolgirls as they march down the street and into the plaza, their syncopated steps, their moves 100% of the Pacific. I am pleased that I can get my damn drone to work, because I am a Neo-Luddite and have no gift when it comes to technology. I am lucky to be able to capture the girls marching down the street, offering a powerful perspective.

Each group carries a hand-painted banner, referring to International Women’s Day and using “Technology for Gender Equality.” I am wishing my mother, girlfriend, daughter, were here to witness this. So I bear witness.

I consider the women whom I have met, some of whom I have befriended, in the three weeks I have been here. Often the deciding factor is my inability to speak the language, and the ability of others to speak English.

Tima, who owns the Lagoon View Lodge with her husband, Timei, is the first woman I meet, and she is warm and friendly, essentially who you would like to be running a lodge. Chuck, my new pal, and former Bostonian, who is also a voyager on the Sea Dragon, has booked a room there, en route to Tahiti. He has stayed a couple days. We both get to meet Tima’s twins, Easter and Nora, both born in Honolulu, but stuck back on Kiritimati when they came home to visit, just before the pandemic. They are sweet, and at 30, still give each other their share of verbal jousting.

At the international women’s celebration, I meet Helena, who approaches me, seeing me wandering around with seemingly no sense of purpose. Warm, friendly, we soon get to chatting, and now I see her regularly, whether at the council house in Tabwakea where I go to get a drivers license, or at the LINNIX government complex, where I can find internet, and VERY spotty telephone.

When I saw her yesterday, she was with her best friend, whom she has known since high school. The best friend was wearing a KGGA T-shirt, and I was intrigued, as the text on the front read GUIDING IS FUN.

I have often referred to guiding in my lectures, for as a college professor that is one of our many functions. I also put that in the context of the many kinds of guides, from bonafide trail blazers, and explorers, to mentors, educators, and those who help. I ask may I take a photograph of the shirt, and then ask what KGGA means. Kiribati Girl Guides Association is essentially their national version of the Girl Scouts. The three of us joke and laugh, after I raise my right hand up, three fingers pointing skyward, thumb holding little finger down, and recite the Boy Scout oath I learned when I was 12. And then the two of them, laughing, and smiling, do the same, reciting their oath. Next time I see them, I will ask them more about the Girl Guides.

I sought out Tureta, learning her name in the course of my seeking a primary school teacher. I figured if a primary school teacher teach these kids English, they would be perfect for me to learn to speak Kiribati. Timei brings me to the primary school she runs, and she and the children are all sitting on the floor, in a ring, as she uses song, and repetition, to teach them, English. She agrees to teach me, tells me when I can return.

Before I see her again, I find myself at BPA – the Kiritibati Broadcast & Publication Authority, as I have realized that I must take this venture seriously, with all the requisite attention to Public Relations I can muster, within my limits. In that sparse, concrete, uninspiring building the man in the folding chair, at the dusty desk, tells me there is an actual writer, who used to do broadcasting back on Tarawa, and that person should interview me. The persons’s name is Tureta.

When I see her for my first lesson, I mention the above, and she is curious about my motivations and purposes regarding an interview. I like her.

Unable to make my next lesson two days later, due to helping prepare for a 70th birthday batoki, when I see her the next day, I’ll explain I am off to Paris for a spell. But I also explained that since I saw her last, I realize that in fact, I should be interviewing her. Her English is excellent, and she is in an online program to earn a degree in English as a second language and preliminary school, with BYU/Idaho. The Mormon influence cannot be underestimated here.

We sit on her buia within her compound that she has had for 20 years, mere feet from the lagoon and talk about any number of subjects for an hour or so. That’s what happened again yesterday, upon my return from Paris, and recovered many more subjects. One of which is her niece, sewing me a shirt from a few yards of fabric I bought locally.

When I meet her niece, and ask about her full-time job, she tells me she is a corrections officer, which reminds me that Tureta and I had that very discussion the week before, when I told her I was interested in meeting women and speaking of their roles in society here. The niece wonders why I am interested in corrections, but I point out that 100 years ago when my grandfather managed the island, there were two police officers on staff, and later my grandfather had to have the mutineers that tried to kill him arrested. There is a method to my madness , and it all stems from connections.

I think of the few days I spent in Poland, of the women I met. The divide of culture and language of course separates most of us.

I have yet to break out my trump card, a small, accordion fold portfolio, maybe 2” x 3”, that I made back in 2005, with photographs of my daughter off and I in the very same pose over the years. Me holding her in everyone of those photographs. I had made it back then, knowing I was going to a conference where people would be asking me about her and I wanted to be able to show them pictures. I’ve carried that small portfolio with me, in my shoulder bags ever since, even though I’ve gone to a few bags since then.

Back in 2000, I found myself in Morocco, about 10 miles from the Algerian border, in a small oasis village on the edge of the Sahara. Again, I was the novelty, and again people stared. I sat in the home of a camel guide, with his family, as they treated me to dinner. As here, we all sat on the floor, in a circle. At that time I had four photographs of my daughter and I, just been taken the month before, for the end of the year, the end of the century. I wore a white dinner, jacket and black tie, my daughter in white sweater, tiny pearls, black pants, big smile, hair pulled back. The photos show us against a white seamless background, holding each other, dancing, smiling. When I pulled out those photographs to show the people in that oasis, in that moment they realized I was more than just a stranger. I was a father.

But I haven’t broken out those photographs here. No need. Family on this island is acute. In Poland, I ask my new friend, 30 year old, Keiti, whose sister lives in Houston, same town as my girlfriend, if the baby she’s holding is hers? No. Somebody else’s baby

I would wager that the way people interact in the mwaneaba in Poland is how they interact in all mwaneabas. Women tend cook fires outside the perimeter. Hammocks hang around the perimeter, with either goods in them, or maybe a father with a baby resting on his belly, both asleep. Men and women play cards in a corner, with more laughter. But always, there are children running and bouncing around regardless of time of day. Or night. Little naked boys, the occasional half-naked girl. Young mothers, with their newborns or other children. Fathers leading sons by the hand, or rocking their own newborns against their T-shirts. Children playing in groups of two, six, many. All laughing and crying and yelling, and occasionally shrinking away.

Four women sit on the floor, weaving banana fronds for the wonderful, long, narrow mats they use on their floors. I have only seen the tan, brown ones, not the fresh green ones that are so pliable. The women work so quickly, rhythm and hands coordinated, with a glance over to a baby sleeping on an adjoining mat. A girl, may be six years old, kisses a baby, several times, sleeping on one of the mats, as her mother weaves. I asked Keiti if this is the girl’s little sister, she says no, that’s just how people are here.

To a person, none are the least bit bothered by my presence, by my intrusiveness, by my taking photos, making films.

I pointedly show them what I have done, and they all smile and laugh, and are pleased. Someday I will find a way to combine what I have done and make sure their village can see them all, every aspect I have captured, see how I appreciate them.

The little boys have their charm, and I’m quick to intercede when one bullies another, as they cluster around me – after church or on a village path.

but I’m a bit take them back when one little boy, maybe five or six years old at most, start raising his hand to me and yelling “FUKYOO!!” it takes me a couple of seconds to wrap my head around how his verbal ejaculation is radically different than all the others. His gesture with raised hand is what gives me the clue. He does not hold up his middle finger, but his index finger. He clearly does not have the whole message put together. But his older brother, a year older does, and his middle finger acts as emphatic punctuation to the phrase neither of them understand at all. What the hell have they been watching?

While both boys and girls follow me around wherever I go, around the mwaneaba, down the narrow paths of the village, at every store or place I stop my motorcycle, it’s the little girls that seems the most precious.

They are usually between the ages of six and 11, the older ones naturally more self-aware, the younger one is completely unaware. They may be in school uniforms, in matching skirts and blouses, or just in underwear, a T-shirt, with some phrase in English, or even a stylish leopard print dress. Their dark hair, walnut eyes, bright smiles against dark skin, remind me of little Portuguese girl I had a crush on when I was in fifth grade.

They also remind me of my favorite painter, Paul Gauguin, who left wife and family behind in France, and moved to the Marquesas in the Pacific to paint. I forget the details, but I do know he either married, or had relations with several young Polynesian girls and women. I think of the New England whalers, the European merchants that found themselves in the Pacific, enchanted by half-naked, smiling women, age not being an issue. Some never went home. With good reason.

Only yesterday I met a man, local, native, in his 40s, and made the mistake of asking if the woman he introduced me to was his daughter. No, it’s his wife. I learned today she is 18. Same age as a daughter of his.

In Poland, Keiti, 30, is younger than my daughter and age is not a factor. She is helpful, fluent in English, happy to help. Knows exactly why I am here. As a matter of fact, I think she can articulate that idea better than myself. I will have to ask her, via Facebook of course, the way every single person on this island, communicates, to write that sentence out for me. But short of that, I will say she speaks of me re-creating memories or something to that effect, and I think that is good enough, as the word creating has been part of my life for as long as I can recall, and though I have barely any memories of my grandfather, his path has guided me on this path.

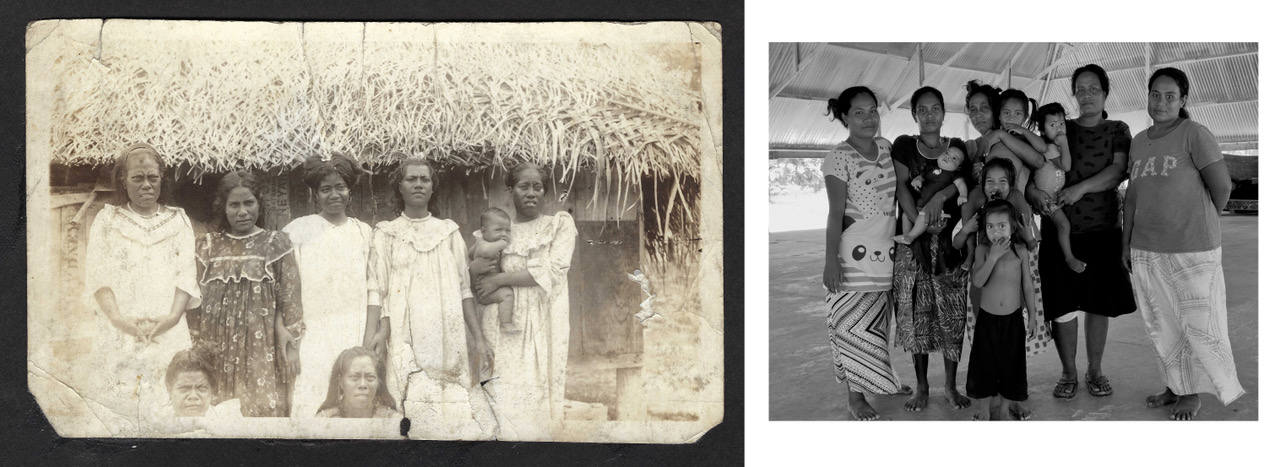

My grandfather took photographs of himself with what I imagine are families. He also took photographs of groups of British civil servants, drinking tea, playing tennis, doing English things in English ways. But it’s his photographs of the groups of men, of the groups of women, standing in front of their homes, that most intrigue me. It is 1916, 1917, and somehow he has charmed them into posing for him. His words, the newspaper articles, refer to them as Tahitians. And yet to a person, everyone here, who sees the photos tells me no, they are Kiribati. I am happy for that, having learned one more detail, that maybe even my grandfather didn’t know.

In some of his photos there are prepubescent girls in grass skirts, arms akimbo in ritual pose, and I’m told they are not Tahitian, not Hawaiian, but Kiribati. Grass skirts, they tell me, were appropriated by others.

There is a little girl in Poland, as beautiful as ever. She shadows me, literally clings to me. I ask where her parents are, and I’m told they are elsewhere. With the other sister. All parents look after all other children, so it’s not like she is neglected. But I think of her clinging, and wonder did some of the little girl, do the same to my grandfather? He was 32 years old, half the age I am now, with his camera, here for work, but finding ways to capture another world to bring home with him.

It’s now 10:36 PM. The music across the street is as loud as ever. It’s Friday night. A girl is on her way to becoming a woman. I think of how my daughter was with me, when the very same thing happened. I was happy she was under my care at the time. We didn’t have a celebration that I can recall. I wish we had.

______________////|__________________////|____

<- Banana / Main Camp || The Frenchmen ->

There is a mythic and cosmic arc between the menses botaki and both the moon and Venus hanging directly overhead.

Tureta the Teacher. Tureta Baniera used to work for the Kiribati Broadcasting & Publishing Association, back in Tarawa. She’s had her own preschool for 20 years now, is working on her online Masters degree in Education/English As a 2nd Language, from BYU/Idaho. There is a very large LDS — Mormon Latter Day Saints — contingent here and in the Pacific.

Tima Kaitaua runs the Lagoon View Lodge, in Tabwakea, with husband Tiemi, here I’m their kitchen, along with grandson, Philip.

Helena Baniera on International Women’s Day, London. The first portrait I snapped. Told me her name was Helena, but weeks later confessed to it being Erena. Damn Anglicizing. Sadly, the 1965 Yashica MAT124G that made the trip, broke. Yet that simplified matters, demanding I only shoot with my iPhone 14Pro, which is a great camera. Along with shooting film, drone, sketching/painting. So didn’t need to haul more gear around.

At the mwaneaba in Poland, I take a crack at emulating my grandfather’s photos. One hundred years ago, people rarely, if ever smiled in photos. I’m trying both. The fact is, the people here laugh so much, it’s often difficult for them to keep a straight face.

Erena on right, with best friend since high school, Abeteka Buraua. Both members of the KGGA (Kiribati Girl Guides Association), at the LINNIX offices.

In Poland a young girl is curious about the I-Matang and his goings on.