Tuesday, 28 March 2023, morning // Fanning Plantation

______//|______//|______//|______//|____

The boat was not sailing toward a destination. No, the Ysabel May she was stationary, and instead the earth was slowly rotating to bring the island to the vessel, to her.

Christmas was coming, as inevitable as a date on the calendar. The relentless waves, the relentless winds, the relentless days that pass and pass. The world turning. His world turning. Ysabel May, axis mundi.

Christmas was coming for Joe, that was certain. What gifts were in store? What gifts did he deserve? He was leaving a world behind. He was hopeful.

The sun broke over the ocean, beaconing a wide fan of light from the horizon, the white silver rays upon the surface indicating the weather that lay ahead.

______//|______//|______//|______//|____

“Greig. That Scotsman would pinch a penny till it begged f’ mercy. The rich stay rich by not givin their money away.”

______//|______//|______//|______//|____

Fanning Island, known locally as Tabuaeran, is one of the main Line Islands located about 1,600 miles east of Tarawa and about 150 miles north west of Christmas Island, now part of Kiribati.

Prior to discovery by 18th Century American and European sailors, the island was used — like Christmas Island — as a way-station for refurbishing vessels, and gathering food and water, by Poylnesians sailing between Hawaii and southerly islands. Artifacts described as those similar to those of Tonga, were discovered in the 1930s by American ethnologist Kenneth P. Emory, of Honolulu’s Bishop Museum. Emory postulates Tongans were on the island in the 1400s. The first non-Polynsian to discover Fanning was the American, Captain Edmund Fanning. From a coastal town in Connecticut, then part of the British colonies, by 24 he was captain of a brig in which he visited the South Pacific for the first time.

Fanning was 29, already a succesful captain and international fur trader, when he came upon the island he named for himself, on 11 June, 1798. Captain of the vessel, Betsey, holding the pelts of 100,000 South American fur seals, he on his way to trade in the markets of Guangzhou (what was then called Canton), part of the Qing Empire of China. Later known as the “Pathfinder of the Pacific,” he sailed around the world several times, and engaged in more than 70 commercial expeditions and voyages. When Fanning stepped foot on his self-titled island, it was only 21 years since fellow Yankee John Ledyard had come ashore on the island named “Christmas” by Captain Cook, in 1777, 180 miles to the southeast.

On 12 June, Fanning then spotted an island he dubbed “Washington,” named for then president of the United States, but did not stop to explore. After an illustrious career, Fanning penned his memoir, Voyages Around the World, published in 1833. Fanning died in 1841, age 72, in New York.

At least 30 whalers visited Fanning Island between the early 1800s and 1860. One was commanded by Captain Mather, who called the atoll “American Island” in 1814.

By 1820 there was to be a permanent population, if even for a few years, as King Kamehameha II of Hawaii deported “50 Hawaiians, foreign deserters and beachcombers” to the island.

An account of the island is given by Captain Legoarant de Tromelin, of the French corvette La Bayonnaise, which visited the island in 1828. He notes the island “was entirely covered with coconut trees” but does not mention any population living there.

The island remained unpopulated until July 1846, when Edward Lucett, a British subject of the Tahiti trading company Lucett and Collie landed with a group of natives to harvest coconuts, considering it a plantation. Coconuts had been planted over the centuries by Polynesians traveling north from the Cook Islands, Tahiti, the Marquesas, on their way to the Hawaiian Islands, for future nourishment. By the 1800s, there were enough to harvest, as they grew well on the rainy island.

Lucett and Collie laid claim to the island and later sold the rights in 1851 to Charles Burnett Wilson, of Tahiti, who later sold the island to Captain Henry English, in 1854. In 1851, Lucett published his 2-volume book Rovinqs in the Pacific from 1837 to 1849.

Lucett’s report notes “a man of Crusoe habits” has already been on the island for some years. This man was believed to be Captain Henry English – he called himself an American and was married to “a Kanaka woman of the Sandwich Islands” (i.e. Hawaiian). Lucett adds in the record that, “this man’s location is on the starboard side of the entrance to the lagoon”, where English Harbour is now situated.

In May 1855 it is reported that there were 200 men, women and children working on Fanning “recruited” by Captain English’s ship Marilda from the northern Cook Islands of Manihiki and Rakahanga, along with a few white personnel. I’ve yet to learn anything about the backgroud of Captain Henry English, no relation to me.

The first time Fanning Island was placed under a national flag was in 1855, as Captain English informally placed the island under British sovereignty, when Captain W.H. Morshead visited on the H.M.S. Dido, on October 16 of that year.

Shipping records in The Friend, The Polynesian, and The Gazette (all published in Honolulu) give some idea of the amount of coconut oil produced on Fanning in those years. In 1859 two vessels arrived at Honolulu with 15,000 gallons; in 1860, one vessel with 10,000 gallons; 1861, three vessels with 30,000 gallons; 1862, four vessels with 44,000 gallons; and 1863, four vessels with 10,800 gallons.

There are conflicting reports about William Greig. One describes him as “a Scot who had a dry goods store in Honolulu, [who] went to work for English as Assistant Manager of Fanning Island.”

Another story suggests “Late in 1857 a US Whaling ship visited Fanning and William Greig a Scot was left there, because ‘he had defied the officers and annoyed the captain beyond endurance’.”

Reconciling those two stories is beyond my scope, at the moment. Regardless, Greig was an intrepid sort, and the sort that could make his own way in the world, regardless of where that world was.

According to the report that Greig was put ashore for being “annoying,” “a few weeks later he was joined [on Fanning] by, Mr H. F. King who was ‘cast adrift’ by his shipmates with a few supplies and by an American George Bicknell from Hawaii, the brother of the Rev. James Bicknell of the Hawaiian Mission.

That two men were forced off boats in the middle of the Pacific within weeks of each other, to then find themselves in league, is quite a coincidence.

It seems William Grieg was originally from county Ayrshire, Scotland. Coincidentally, John Bryden, from the town of Ayr, now living in Tabwakea, left Scotland about 100 years later for the South Pacific. Oceania is rich with the lineage of Scotsmen.

Greig, King, and Bicknell all married Polynesian women. Greig’s wife was Teanau Atu (1842-1917), sister of the king of Manihiki, of the Cook Islands. C aptain English formed a partnership with Greig and James Bicknell in 1859. Their coconut/copra prospered. Operations eventually branched into several other endeavors including guano, beche de mer, ship repairing, victualling and honey production.

In 1864 English sold his share of the islands to Greig and Bicknell and left due to ill health. Greig took charge of Fanning, while Bicknell managed Washington Island. They imported laborers from various Pacific islands. There is a report several of the recruited were “repatriated Peruvian slaves.”

What this refers to is the nefarious practice of “blackbirding,” where colonial vessels would kidnap native islanders, bringing them anywhere from Australia to Peru, to be enslaved workers. In this instance, it is also reported that “At the expiration of their contract it was arranged with Hirham Bingham II, “the Apostle of the Gilbertese”, for the Hawaiian Mission’s Morning Star to return them to their homes on her next voyage to the Gilberts and the Fanning Island Co. contributed $450 in passage money and food for the group.” Bingham, born in Honolulu to the Yankee missionary for whom he was named, was the first to translate the Bible into Gilbertese.

This 1864 reference is the first note I’ve found introducing Gilbertese to the Line Islands, but just because that’s the first record I’ve found does not make it true, as there may have been others before.

In 1874 it was reported that “Tahitian” laborers were used. “Tahitian” is often used loosely for any Polynesian indentured laborers, much as the Hawaiian word “kanaka” was often used when referring to natives. However it was noted by James Bicknell, the nephew and later heir to his uncle’s share of the operations, that Manihiki laborers were used in 1882, and in 1894 the laborers were Gilbertese.

George Bicknell died in 1884 leaving his share of the plantation to his brother, James Bicknell, then the auditor of the City and County of Honolulu.

However William Greig continued to operate the copra production industries on both Fanning and Washington islands with his large family of four sons and five daughters until his death in 1892. Greig was buried close to the southern entrance point of English Harbour.

The elder son, George Greig, took over the management, working it along with brothers James, Hugh, and Willie. James Bicknell remained in Honolulu and was considered half owner of the islands by the Greigs.

Meanwhile, in other parts of the world, grand schemes were in place.

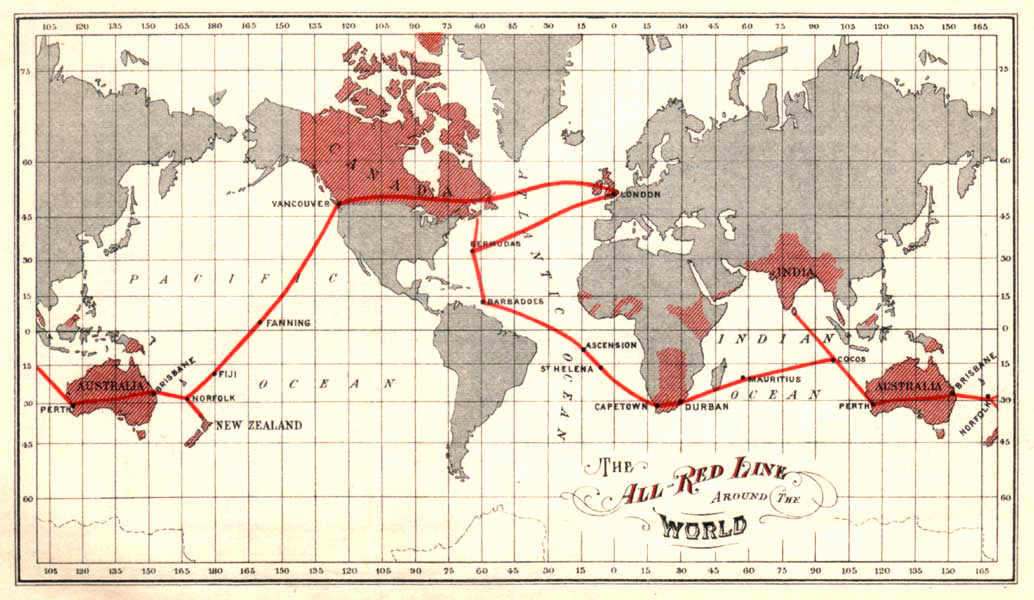

Fanning Island — already flying the British flag — was annexed by Great Britain, in 1888 when plans were being drawn up to lay a telegraph cable across the Pacific, as part of the All Red Line. The British belief was the Empire was best served with the majority of cable relay stations placed on British territory (the cable from Singapore to Australia ran throught Java, a Dutch colony). The informal name derives from the common practice of colouring the territory of the British Empire red or pink on political maps.

In 1896 The Pacific Cable Committee was formed and Captain A. Mostyn Field, of HMS Penguin was given the project to report on the suitability and capabilities of Fanning and Palmyra Islands as a submarine cable station. In his report dated August 6, 1897 Mostyn determined Fanning more suitable, and mentions the Island is owned by Mr. George B. Greig.

The ALL RED LINE.

In brief, once the working telegraph was introduced in 1839, inventors were already considering ways to have the lines cross bodies of water. Massachusetts-born Samuel Morse — inventor and painter — created his code for telegraphy in 1837 and by 1840 was discussing submerging lines. By 1842 Morse submerged lines in a New York harbor, and transmited clearly. In 1850 the first commercial wire to cross a substantial body of water was to cross the English Channel, linking Britain to the Continent. By 1858, the first cable stretched across the Atlantic Ocean, from Ireland to Newfoundland, though it only lasted three weeks, before malfunctioning. October of 2021 I found myself in Hearts Content, Newfoundland, the site of the the second successful spanning of the ocean, in 1866, and what was the first hub of the telegraph in the Americas.

The British Empire’s telegraph cables extended from Great Britain, via the continent, to Suez, Egypt by 1870. From there to Madras, India, to Malaysia, and to Singapore. Australia was connected in 1871, with New Zealand connected in 1876. At the 1887 Colonial Conference in London, there were four key points considered: Imperial co-operation, world-wide Naval defence, the Pacific telegraph cable, and the Royal title. It was at this month-long series of meetings that Victoria had her title legthened to “Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain, Ireland, and the Colonies, and all Dependencies thereof, and Empress of India.” A more beneficial aspect of the conference, with the idea of creating better communication between all member states of the Empire, was a proposal to lay a cable from Canada to Australia, which was approved.

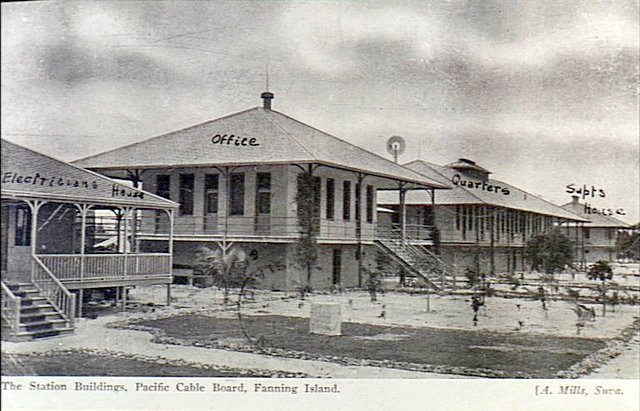

By 1902 a cable relay station was established on Fanning, breaking the stretch of undersea wire from Bamfield, Vancouver Island, Canada, to Suva, Fiji. The former length spanned 3,300 miles, and 14B the latter spanned the remaining 2,200 miles.

Prior to this time, any communications off the islands was in the form of letters, given to the captains of vessels calling at the island to load coconut oil, copra or to bring in or repatriate native workers. The letters were then entrusted to the plantation’s purchasing agents abroad, who then stamped them and forwarded them through the postal system of the arrival country.

Not long after the installation of the All Red Line’s cable relay station, now well staffed by sharp, white-uniformed officers of the British Empire, in 1903 Humphrey Berkeley, of Suva, Fiji, obtained an option to purchase Bicknell’s share in the islands and attempted to interest the English soap manufacturers, Lever Brothers, in acquiring them. Levers wished to obtain copra plantations in the Pacific to supply their soap manufacturing business, as they already held intersts from Africa to Australia, for both palm and coconut oil.

Financial difficulties, already apparent before the legal battle, reached a head in 1907 and 1908 when creditors took legal steps to obtain the return of the money they had advanced. Proceedings in Suva resulted in the sale of both Washington and Fanning Islands for debt. The purchaser was the shrewd 10 French priest, Petrico Emmanuel Rougier, of Fiji, who had renounced his ministry and had entered the world of commerce, having “aquired” a fortune that had been inherited by a former French convict, Gustave Cécille, whom he helped.

Rougier quickly became a plantation owner, buying the two islands for 25,000 pounds in 1909. Within six months he was in discussions to sell the islands to Japan, but instead sold them to a London concern, for 70,000 pounds. The reason for selling? Rougier bought Christmas Island in 1912.

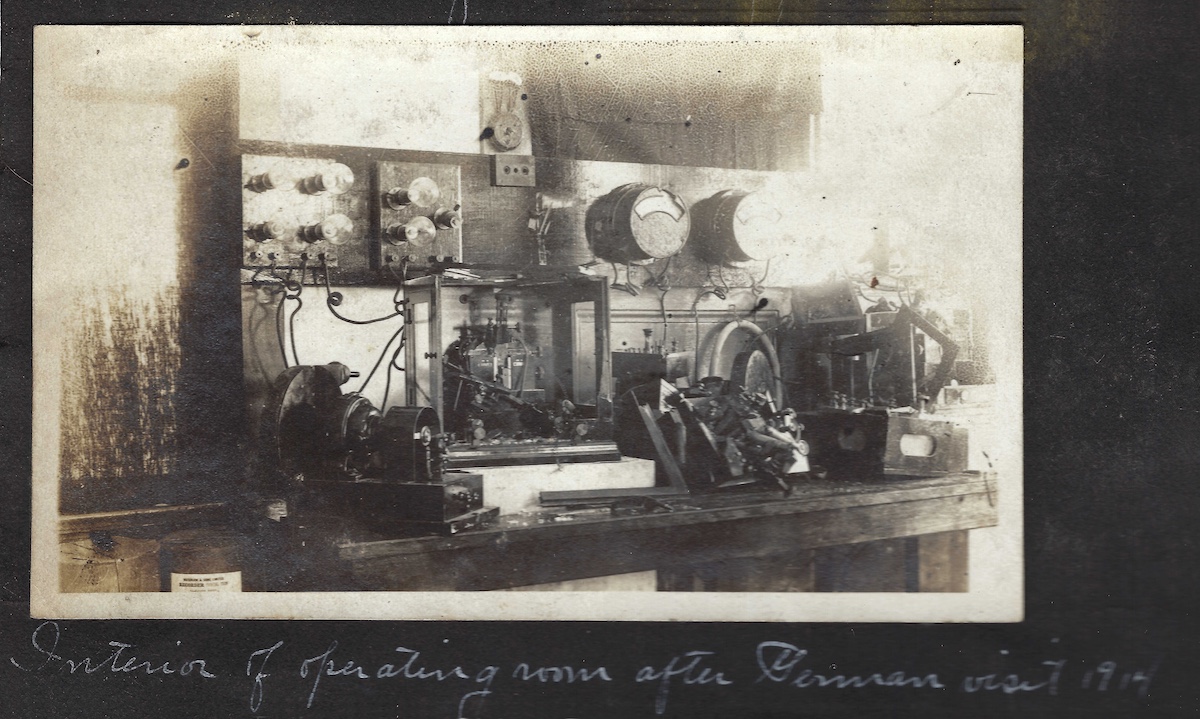

On September 7, 1914, the Great War well underway, the German cruiser Nurnburg, accompanied by SMS Leipzig, slipped up to Fanning, flying a false French flag. They landed an armed party and wrecked the cable station, cut the two cables, and destroyed a cache of spare instruments. They also took 3000 gold sovereigns from the safe, used to pay the staff, plus £71 in stamps and cash from the Post Office.

With the assistance of Hugh Greig, who dived for the several ends of the cable, communication was re-established within two weeks. Shortly after this incident the Nurnburg was sunk, with all hands, in an engagement with the Royal Navy known as the Battle of the Falkland Islands.

In 1939, it was reported that the island was being fortified against a repetition of this but the report was later denied, it being stated that an undefended island of purely commercial importance was safer. That same year, the atoll was incorporated into the British colony of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands. The cable relay station closed in 1963, and in 1964 it was taken over by the Hawaiian Oceanographic Institute as a Pacific Equatorial Research Laboratory for the study of Equatorial Currents. In 1979, Fanning Island gained independence, becoming part of the Republic of Kiribati, and was renamed Tabuearan Atoll.

______//|______//|______//|______//|____

______________////|__________________////|____

<- Music to Read By || The Ends of the Earth, at the Ends of the Earth ->

Fanning island, now called Tabueran. There was a brief period when the atoll was called American Island, as seen in this detail from Gray’s Atlas, Map of Oceanica, 1873. Captain Mather, of the schooner America, named it American Island in 1814. Though the British took possession of the island in 1855, the name American Island still shows up in this 1873 atlas. It’s 185 miles from London, Christmas Island, northwest to English Harbor, Fanning Island. That’s a two-day sail, if the conditions are good. And if you know how to sail.

Fanning/Tabuaran, though only less than 200 miles from Kiritimati has a much wetter climate, making it a far superior environment for growing coconuts, though that was not surmised in the early 20th century.

The Betsey Returning Into Port, 1833. It was upon this vessel, loaded with seal furs, heading for Guangzhou (Canton), China, from along the coast of the Americas, that Fanning and crew spotted an island not on any previous map. Captain Fanning was known as “The Pathfinder of the Pacific.” Who called him that, where it was first published, I’ve yet to ferret out.

Sketch, circa 1785, for William Daniell's 1806 The European Factories, Canton and Hongs at Canton, a reverse-glass export painting of the Thirteen Factories in Guangzhou China in 1805, unknown Chinese artist. The Thirteen Factories, or Canton Factories, were the sole shops and warehouses allowed for foreign trade, from 1757, through 1842. The factories eventually fell victim to fires, the last one during the Second Opium War.

There are no likenesses of Captain Henry English, who arrived on Fanning in 1848, and bought the island in 1854. I’m assuming he’s British, as he placed the island under British protection when HMS Dido arrived in 1855. Little is known about English — no relative of mine — other than his arriving on the island in 1855, with 50 laborers from Manihiki (Humphries) Island, to begin producing copra and coconut oil. The harbor is named for him.

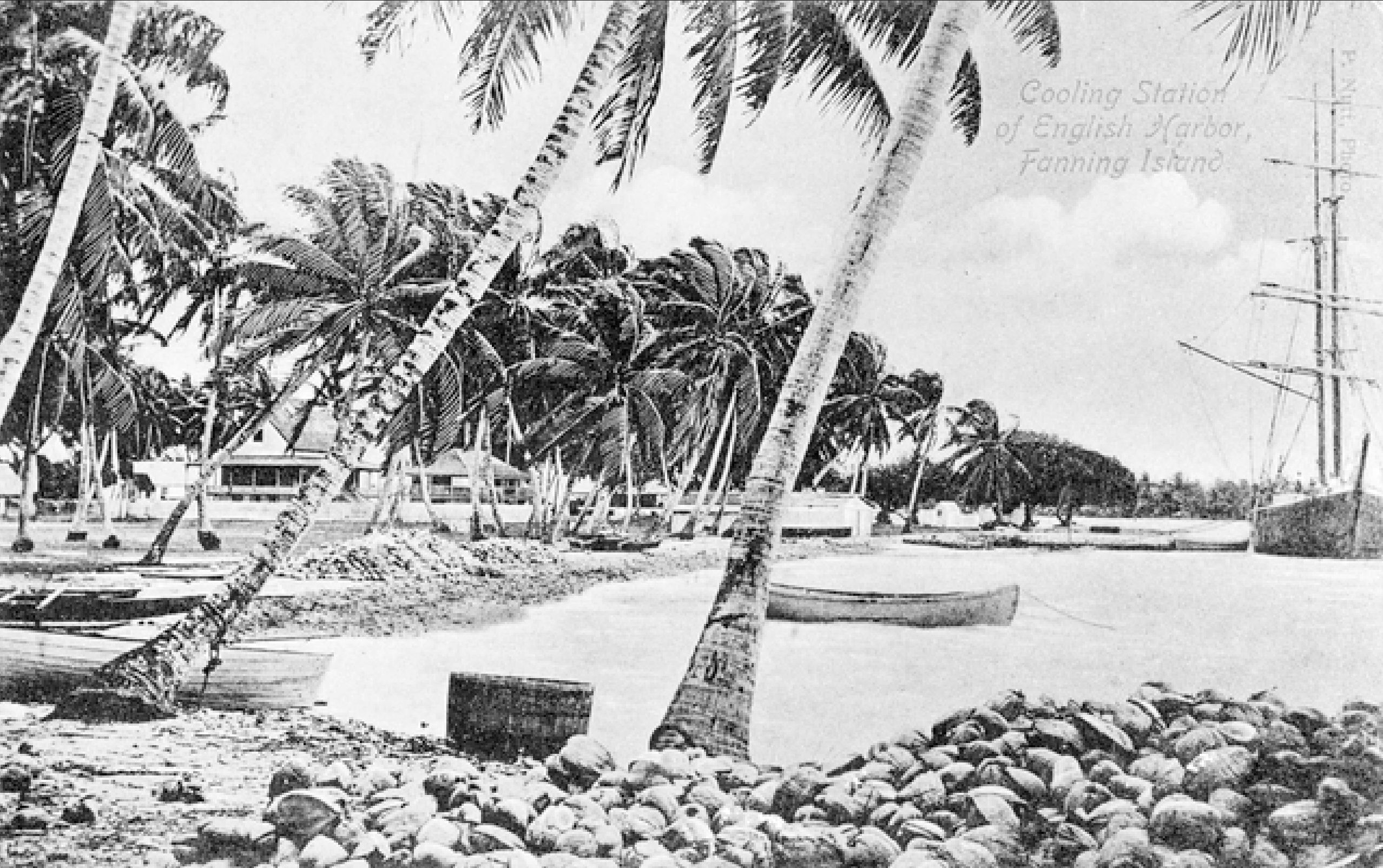

The cooling station of English Harbor, Fanning Island, on an early 20th century postcard. What is a “cooling station”? I have yet to ferret out this information.

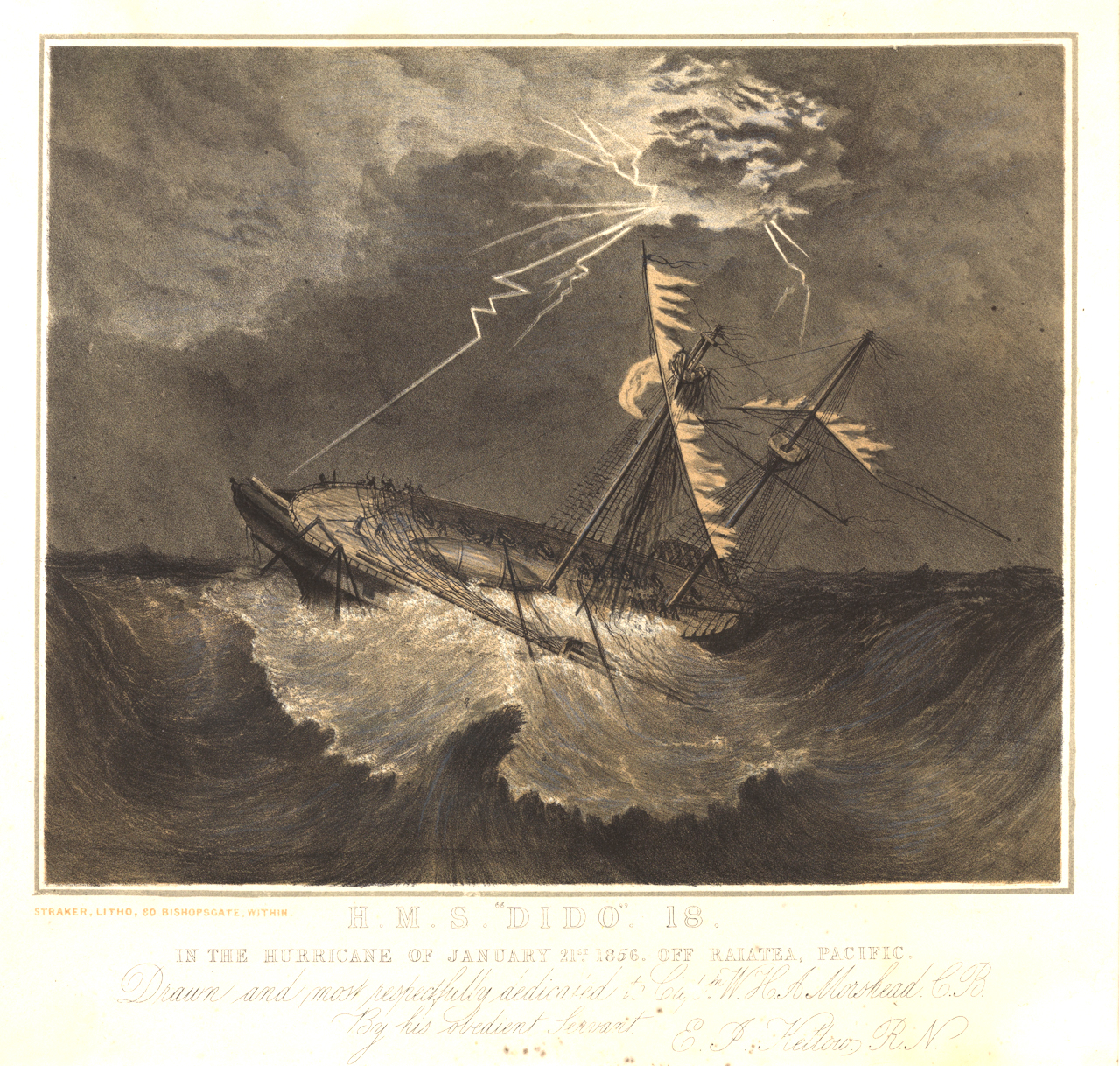

HMS DIDO (18 GUNS) Casting from Spithead, 1841 and the Hurricane January 21st, 1856, gives an indication of winter storms in the Pacific.

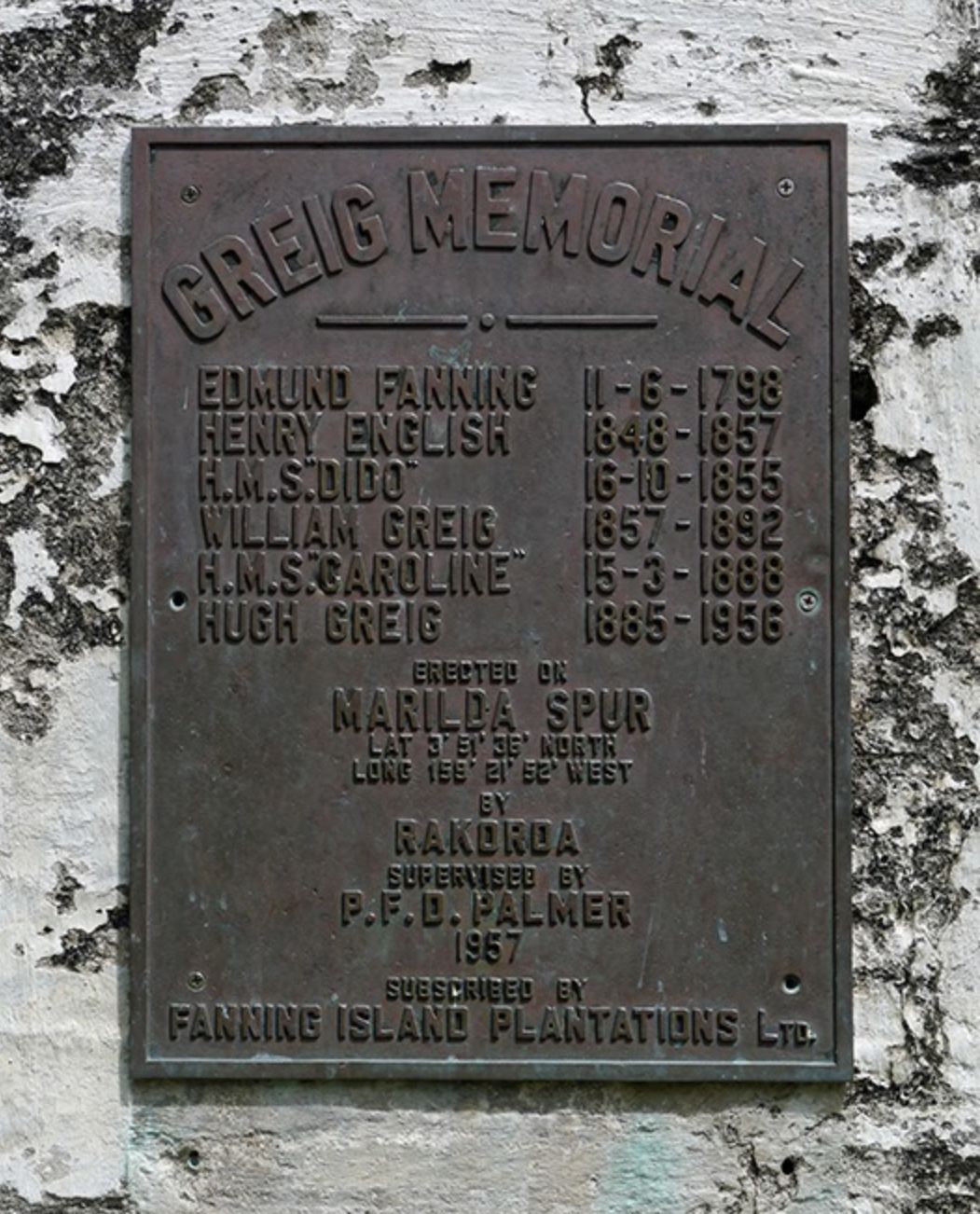

The Greig Memorial plaque on Tabuearan, from 1957, just more than one hundred years after Henry English took possession under the Union Jack on the Dido, in 1855. The plaque was pilfered within the last decade.

There’s no photo of William Greig, patriarch of so many in this area of the Pacific, but my grandfather captured William “Willie” Greig, in this 1919 photo from his photo album. Grieg is fourth from the left. “Head of Fanning Island Copra company with staff and British Commissioner also Hertolet F.P.C.P.”

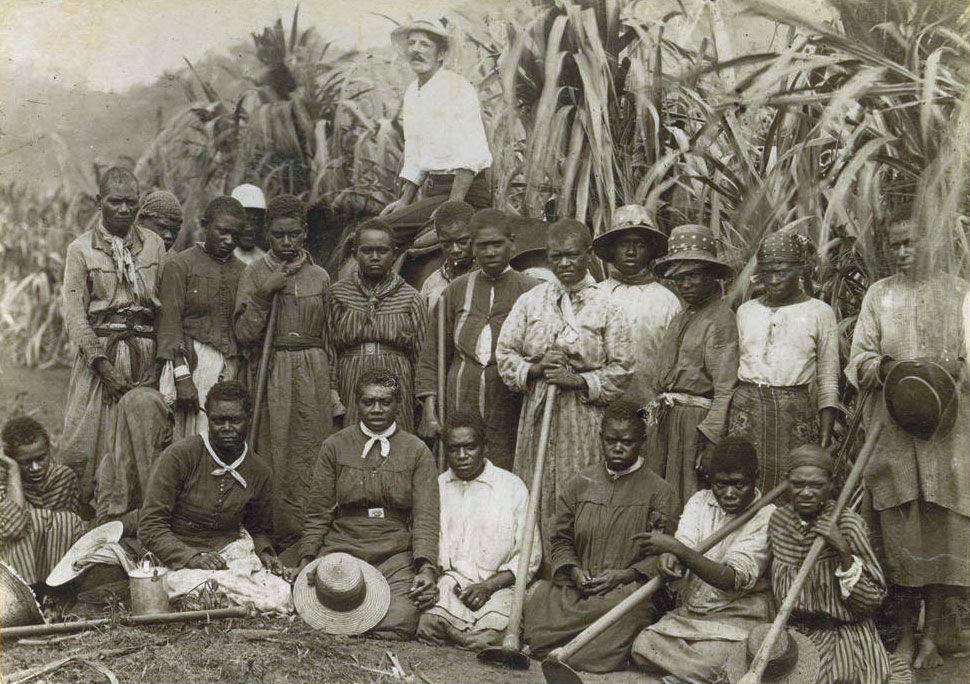

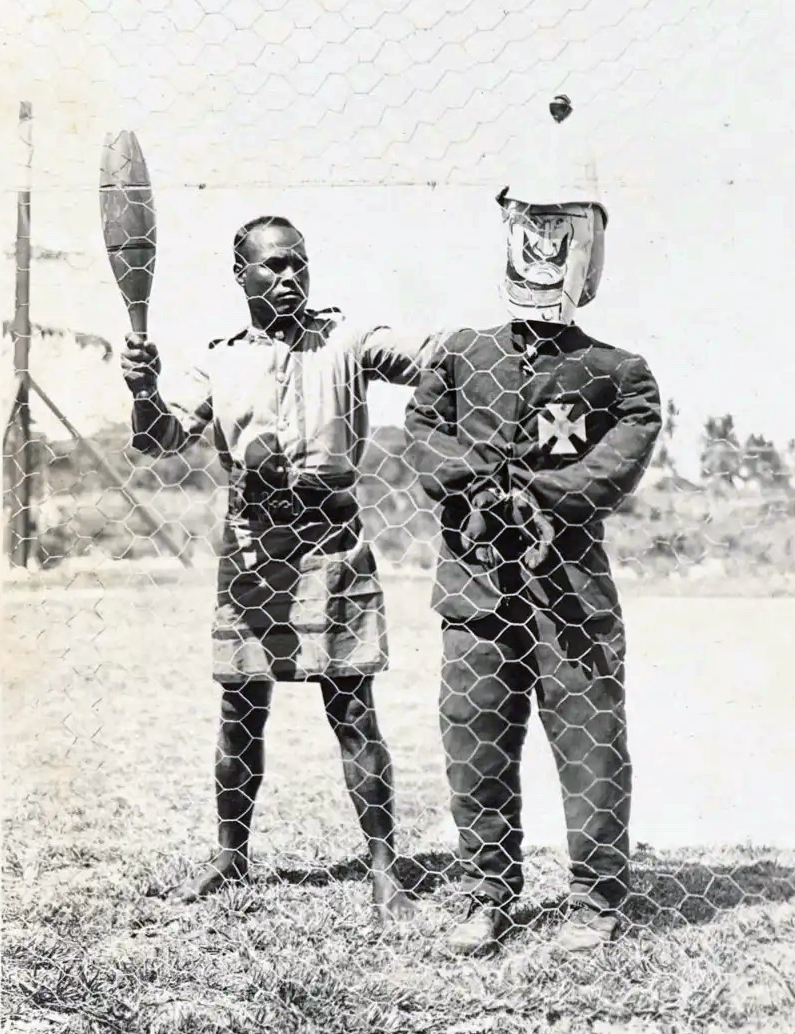

The nefarious practice of “blackbirding” was but one method of furthering colonial control. Seen here, South Pacific islanders (Kanakas), with an overseer (background), on a sugar plantation, Cairns, Queens., Australia, c. 1890, and a photograph depicting blackbirding of Indigenous South Pacific islander peoples, c. 1890. Photographs from, respectively, the John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland and the National Library of Australia.

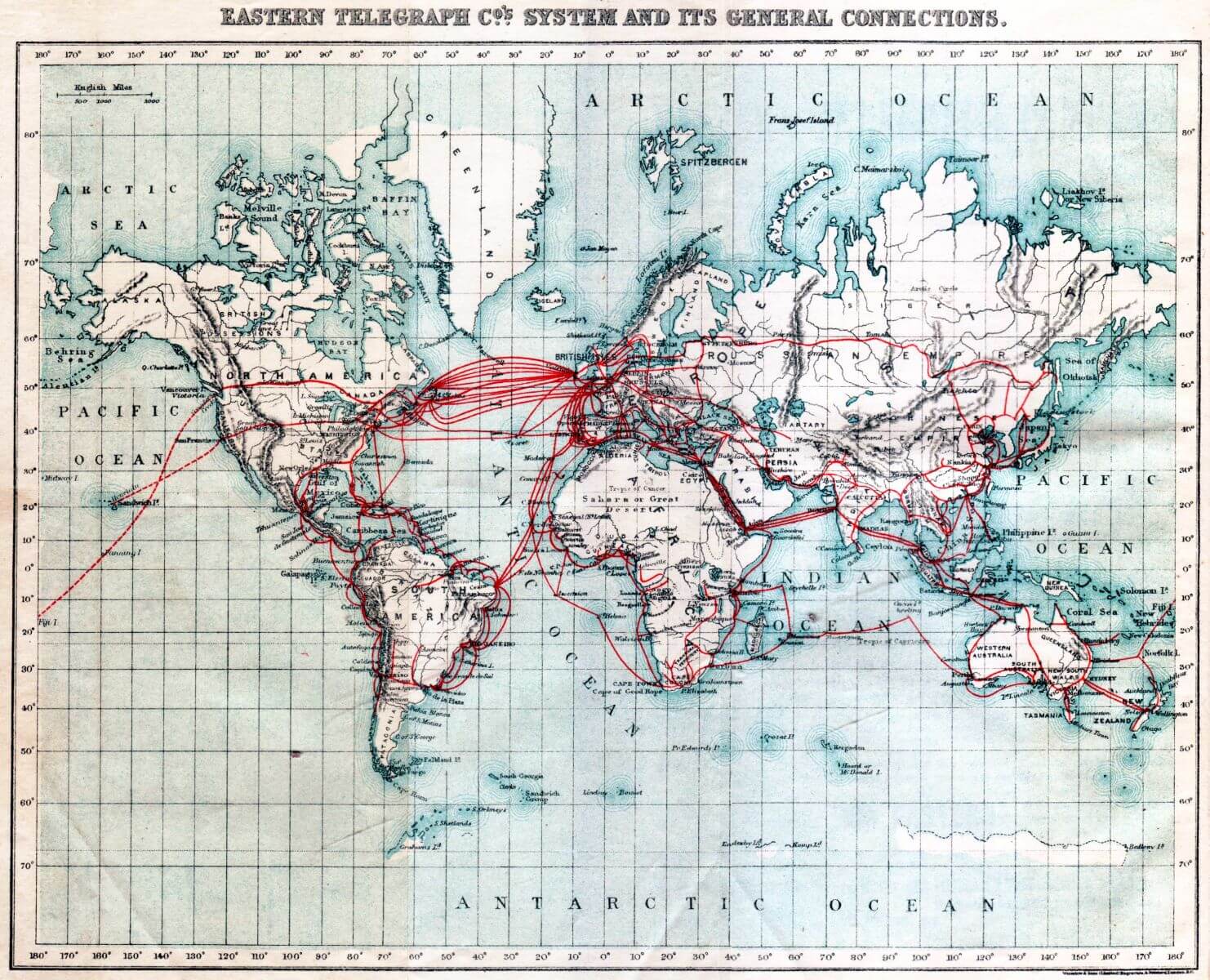

This map, from 1901, from The Eastern Telegraph Co., shows existing — and planned — cable routes, around the world.

By 1902 the All Red Line, which connected the British Empire, had reached Fanning Island, the lone cable station on terra firma between Vancouver, Canada, and Brisbane, Australia. With this final stretch of communication, the British now could communicate around the globe.

A postcard showing the Station Buildings of the Pacific Cable Board on Fanning Island. On the left is the electrician's house, the large office building in the centre next to the staff quarters and on the right is the Superintendent's house. Photo by Alice Mills, circa 1914-1918.

This 1914 panorama of Fanning, taken by W.R. Peters, may show the Western Point, with the lagoon to the left, based on shadows indicating the sun is to the right, and therefore the south. Peters was the "official" photographer at the Fanning Island cable station, from 1914-1920. He captured the events of September 7th, 1914, when the German ship Nurnberg destroyed the cable station in an early act of aggression in W.W.I.

Joe English took this photo, upon his rescue. He was at Fanning for two weeks, before catching a boat to Honolulu. Based on the number of photos in his album of tennis matches, it was clearly a beloved pastime on the island, complete with tea service.

The German cruiser SMS Nürnberg motored within shelling distance of Fanning Island, on 7 September, 1914. Soldiers came ashore under a French flag, and wrecked the British cable relay station, as well as cut the cable that stretched from Vancouver to Australia. The was repaired within weeks, lead by Willie Greig. Less than two months later the Nurnberg had been sunk off the Falkland Islands.